2024 Year of Elections: How South Africa and Botswana’s Votes Defied Expectations

Writer and researcher, Alex Daniels, compares the 2024 elections in South Africa and Botswana, exploring how two long-dominant parties lost support in strikingly different ways.

As a writer and researcher for the Backbench Podcast, a student-run political podcast at the University of Edinburgh, I was recently tasked with researching an election or two from 2024. I chose to research the elections of South Africa and Botswana so I could compare and contrast the two as examples of long-dominant parties losing support, as is consistent with global themes of anti-incumbency and voter dissatisfaction throughout last year’s elections. In South Africa, the African National Congress [ANC] has ruled since South Africa’s liberation from apartheid in 1994. Meanwhile in Botswana, the Botswana Democratic Party [BDP] has ruled since Botswana’s independence from the UK in 1966. Until 2024, that is. Knowing both these parties suffered shock defeats after decades of unparalleled dominance, and that these are neighboring countries in southern Africa that are both former British colonies, I expected the 2024 elections of these two states to have a lot in common. But my primary surprise was that the similarities that appeared at surface level were all the similarities there really were; the two elections were far more distinct and nuanced than I had thought.

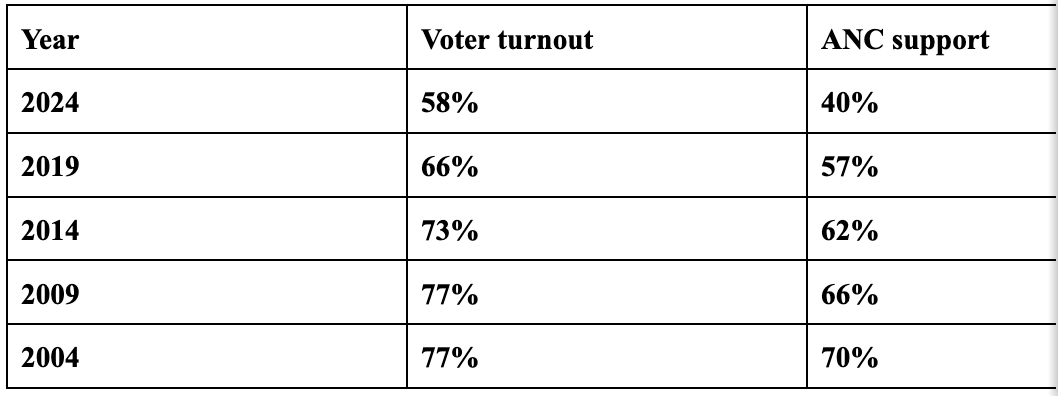

South Africa uses proportional representation to elect the 400 members of the National Assembly, with the leader of the majority party becoming President. The ANC’s vote share had decreased incrementally each election since the turn of the century, but in 2024 its vote share declined substantially, from 57% to 40%. See the table below.

For the first time since the fall of apartheid, in 2024, the ANC failed to secure a majority, throwing its future into doubt. However, because the party nonetheless retained a plurality of support, it was able to form a coalition agreement that would see ANC leader and incumbent President Cyril Ramaphosa retain his position for a second term. The ANC lost support primarily due to its failure to deliver services [such as low electricity supply leading to consistent blackouts], in addition to various corruption scandals. The ANC has historically been so popular because the majority of South Africans had been liberated by the party and thus felt they owed the party their vote. However, as more time progresses since 1994, a new generation of voters did not experience the horrors of apartheid and is thus not predisposed to vote ANC. All they have experienced is policy failures and corruption scandals, leading to rising voter dissatisfaction that culminated in the South African electorate determining last summer that the ANC could no longer be trusted to rule outright. As a result, the ANC formed a government of national unity with the DA and two smaller parties, which allowed Ramaphosa to retain his role as President.

The ANC was founded in 1912 to advocate for the rights of Black South Africans, and resisted apartheid and white minority rule through both political and military means until the end of apartheid in 1994. Today, the ANC is generally a catch-all party for those opposed to apartheid and racial discrimination, but is broadly centre-left and social democratic. In this way, the ANC is similar to the Scottish National Party, which is vaguely centre-left but upholds its foremost goal of Scottish independence above any socioeconomic partisan ideology.

Other parties include the Democratic Alliance [DA], uMkhonto we Sizwe [MK], and the Economic Freedom Fighters [EFF].

The DA is a centrist party that has finished in second place in each of the last five elections. The DA enjoys high levels of support from White South Africans and has been the most consistent party to successfully market itself as a safe alternative to the ANC. In 2024, the DA picked up 22% of the vote.

MK, whose name means Spear of the Nation in Zulu, is a populist party founded in December 2023, mere months before South Africa’s elections. MK copied the name and logo of the former armed wing of the ANC fighting against apartheid. The ANC sued MK over this- and lost- but that isn’t even the most controversial bit of MK’s rise. Jacob Zuma, a lifelong ANC member who served as the fourth President of South Africa from 2009-2018 [Ramaphosa succeeded him in 2018], campaigned with MK before becoming the leader of the newly established party, leading to his expulsion from the ANC for campaigning with a rival party. MK’s platform is an unorthodox combination of socialism and far-right social views, with a healthy dose of Zulu nationalism. The rise of MK contributed to the ANC’s loss of a majority, making inroads into the ANC’s traditional base and picking up 15% of the vote.

The fourth and final party to have picked up more than 5% of the vote is the EFF, who won 9% in 2024. Like MK, the EFF are a party that splintered off from the ANC over economic mismanagement and corruption scandals. Unlike MK, the EFF is hard-left, both socially and economically. The Communist and Black nationalist party is anti-Zionist to the extent that it is actually explicitly pro-Hamas, stating that if the EFF won the election, they would sell arms to Hamas. The EFF also supports Russia’s war against Ukraine.

So, to recap, governance failures and corruption scandals saw the ANC lose its majority in 2024, as voters faced economic grievances such as record unemployment. However, the DA retained its plurality of the vote share and was able to form a government of national unity, meaning ANC leader Cyril Ramaphosa will be President for a second term.

Meanwhile in Botswana, the Botswana Democratic Party [BDP] had been ruling for 58 years, the longest uninterrupted streak in the world. The BDP is broadly centre-right, but has consistently upheld values of economic development, democracy, and national unity above any partisan ideologies.

Diamonds were discovered in Botswana in 1967, just one year after independence. Under the leadership of the BDP, Botswana used their diamond reserves to build infrastructure and fund social welfare programs, leading to their consistent reelection. Botswana is generally considered one of Africa’s brightest spots due to its stable democratic government, its high levels of economic and social development, and its consistent good governance. Despite struggles including the global downturn in the diamond market and rising unemployment, Mokgweetsi Masisi’s BDP government was nonetheless projected to win last year’s elections yet again. But stunningly, the BDP won just 4 seats, relegating the once-dominant party to the status of fourth-largest in Botswana. How did this happen?

So Botswana uses first past the post [FPTP], the same non-proportional system as the US and the UK, to elect most of the 69 members of the National Assembly. When the BDP’s support started to decline slightly in the 90s, FPTP kept the BDP afloat because the BDP enjoyed broadly high support from across the country rather than intensive support in only specific regions. This matters because it means the BDP narrowly finished 1st in most constituencies, rather than dominating a few and finishing 2nd in the rest. Anyway, in 2024, the BDP won 30% of the vote. Under proportional representation [PR], the BDP would've won about 20 seats. But because of FPTP, the BDP only won 4 seats. This is because that trend has flipped- the BDP is now consistently finishing in second place across the country. This segues into an argument in favour of PR, which is not what I am here to discuss.

So, who stood to benefit from the decline of the BDP? Primarily the Umbrella for Democratic Change [UDC], an alliance of three centre-left to left-wing parties who united to unseat the BDP. The UDC won 36 seats, enough to establish a non-BDP government for the first time in Botswana’s history. Duma Boko, the leader of the UDC’s largest party, peacefully replaced the BDP’s Mokgweetsi Masisi as President of Botswana. Two other parties, the Botswana Congress Party and the Botswana Patriotic Front, also made inroads into the traditional hegemony enjoyed by the BDP, winning 15 and 5 seats respectively.

Although it struggles to explain such a dramatic shift, one argument is that Masisi and the BDP were primarily relying on incumbency, while the UDC promulgated exciting new policy proposals, such as more than doubling the minimum wage, improving social services, and creating a more independent judiciary. It could be the recent economic struggles, it could be the UDC’s new policy proposals, or it could just be that 58 years was enough. Either way, it can be said without a shadow of a doubt that no election more dramatically exemplifies the anti-incumbency trend of 2024’s elections as Botswana.

I said at the beginning that I had expected the South Africa and Botswana elections to be relatively similar, and that that was why I had chosen to research them. However, they were far more different than I had expected.

Firstly, Cyril Ramaphosa and the ANC stayed in government, while Mokgweetsi Masisi and the BDP were handed a debilitating defeat, leading to a wholesale change of government.

Secondly, voter turnout, which decreased consistently in South Africa, as previously mentioned, but stayed high in Botswana, clocking in at 81% in 2024.

Finally, populism and extremist politics were prominent in South Africa with the MK party [and to a lesser extent, the EFF]. But no party in Botswana seemed to be massively left or right of the centre. If I had to guess, I would attribute this to Botswana’s context. Voters may not feel they need to turn to a radical fringe party if there is a large centre-left party who has itself never been in government and is thus not to blame for the incumbent party’s shortcomings.

I had a lot of fun researching and writing this, and I hope anyone who has made it this far found it to be worth their while. Thank you for reading.

Sources

https://data.ipu.org/parliament/BW/BW-LC01/election/BW-LC01-E20241030/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c238n5zr51yo